The Case Against Depicting this in the 30’s or 40’s

I’m going to go ahead and assume familiarity with The Little Prince. Anyone who is not familiar with the story can read up on it here.

One of the problems with staging the Little Prince is the general sense of nostalgia present in the source material. Make no mistake though, this story is timeless and that’s one of the reasons that it remains popular.

The second reason it remains popular is it’s one of those stories that is appealing to children but is really meant for adults.

Let me go ahead and address this nostalgia issue. The Little Prince draws inspiration from the author’s experiences being stranded in the desert following a plane crash in 1935. Interestingly this crash was a result of an attempt to break the speed record for the Paris-to-Saigon. However, when The Little Prince is staged it seems that designers pay more attention to the 1935 part of than to the speed record attempt part. This is understandable; Doubtless they are drawing heavily off of the book which was published in 1943 and the life of the author, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, who later served and died during the Second World War.

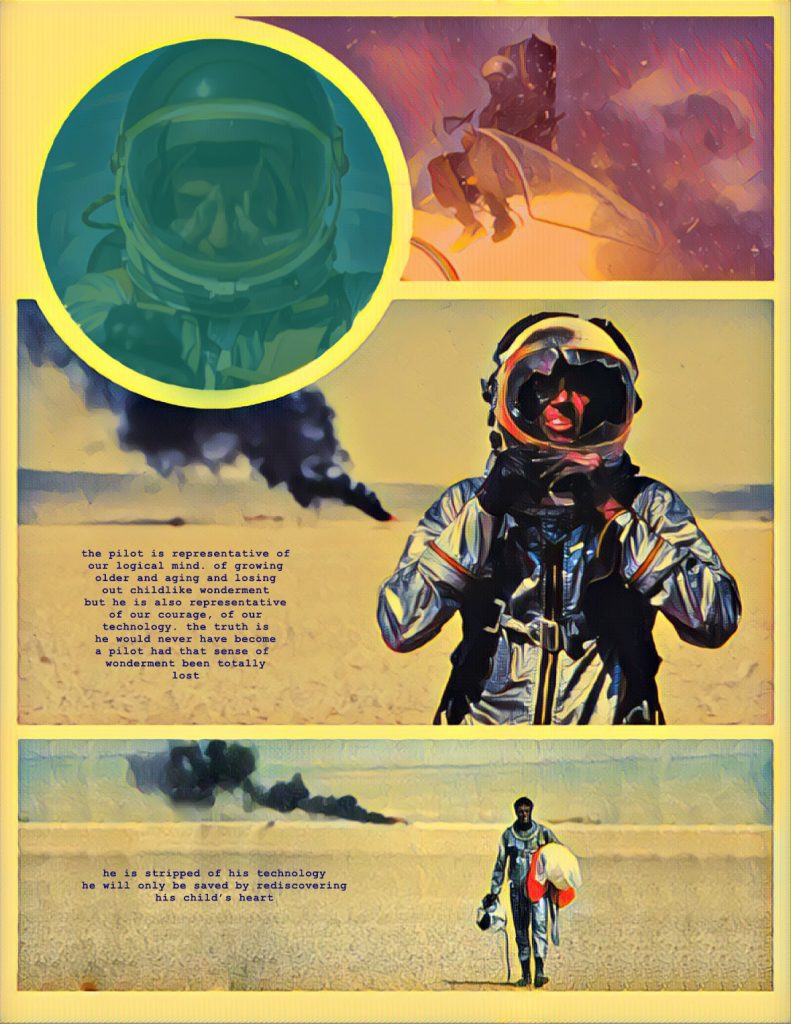

So why is that a problem? Why am I specifically rejecting that particular sense of nostalgia? Why do I see a silver suited test pilot walking through the desert dragging a parachute rather than a leather helmeted, goggle wearing pilot sitting next to his prop plane? Well, simply put, because I’m an American and I want to design this for an American audience.

See, we have this nostalgia problem in America. It’s not a typical nostalgia problem where we look back at our childhood with rose tinted lenses. Sure, the part of the 70’s and 80’s that I remember will always be wonderful because my brain was a sponge back then and everything was a cause for wonderment. No, our national problem is more closely related to what the poet Hesiod describes in Works and Daysas the ages of man.

Hesiod describes a general degradation of society by assigning 5 ages of man

The Golden Age

The Silver Age

The Bronze Age

The Heroic Age

The Iron Age

Each age is worse than the previous age with the notable exception of the Heroic Age, which Hesiod describes in the following way:

“…Zeus the son of Cronos made yet another, the fourth, upon the fruitful earth, which was nobler and more righteous, a god-like race of hero-men who are called demi-gods, the race before our own, throughout the boundless earth. Grim war and dread battle destroyed a part of them, some in the land of Cadmus at seven- gated Thebe when they fought for the flocks of Oedipus, and some, when it had brought them in ships over the great sea gulf to Troy for rich-haired Helen’s sake: there death’s end enshrouded a part of them. But to the others father Zeus the son of Cronos gave a living and an abode apart from men, and made them dwell at the ends of earth. And they live untouched by sorrow in the islands of the blessed along the shore of deep swirling Ocean, happy heroes for whom the grain-giving earth bears honey-sweet fruit flourishing thrice a year, far from the deathless gods, and Cronos rules over them; for the father of men and gods released him from his bonds. And these last equally have honour and glory.” (Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, 1914)

Hesiod, unfortunately, was born into the Iron Age in which everyone seems to fall short of the standard set in the Heroic Age, where

“…men never rest from labour and sorrow by day, and from perishing by night; and the gods shall lay sore trouble upon them. But, notwithstanding, even these shall have some good mingled with their evils. And Zeus will destroy this race of mortal men also when they come to have grey hair on the temples at their birth . The father will not agree with his children, nor the children with their father, nor guest with his host, nor comrade with comrade; nor will brother be dear to brother as aforetime. Men will dishonour their parents as they grow quickly old, and will carp at them, chiding them with bitter words, hard-hearted they, not knowing the fear of the gods. They will not repay their aged parents the cost their nurture, for might shall be their right: and one man will sack another’s city. There will be no favour for the man who keeps his oath or for the just or for the good; but rather men will praise the evil-doer and his violent dealing. Strength will be right and reverence will cease to be; and the wicked will hurt the worthy man, speaking false words against him, and will swear an oath upon them. Envy, foul-mouthed, delighting in evil, with scowling face, will go along with wretched men one and all.”

So there’s Hesiod’s ancient Greek “kids today” moment, railing against contemporary ethics and rejection of morals, while simultaneously praising an earlier generation. If it sounds a little familiar it’s because this is something of a generational tradition. Yet Hesiod isn’t exactly saying his generation was better. He’s saying the Heroic Age was better. THEY were the best. THEY were the true heroes. He’s not just yelling from his porch, he’s gone full Tom Brokaw…

If I ask an American what was our greatest generation, I’m generally going to get the same answer (hint: the answer is in the name). Now this is problematic for a few reasons, the first of which is that it reeks of hubris. Yes, the accomplishments of our “Greatest Generation” were significant but it sets this generation above all preceding generations and holds it up as a sort of unattainable bar for succeeding generations. Yes, your generation may accomplish much but it will never be the “greatest”.

Semantics aside, there is a much bigger problem with this idea of a “greatest generation.” What exactly did this “greatest generation” accomplish? Well, a lot actually. They were certainly involved in the Space Race (which I reference heavily in my concept of the Pilot- Before he was a test pilot Chuck Yeager was an Ace over the skies of Europe.) But no, there were other people involved in the Space Race, and actual space travel fell upon a new generation of pilots too young to have served in World War 2. When we speak of the accomplishments of the Greatest Generation, we’re really talking about one thing. Their actions in Europe and in the Pacific during the Second World War. As time passes those actions become more and more glorified, until it’s become a given that this generation of Americans basically saved the world. Never mind that this truth comes at the expense of everyone else who fought against the axis powers (especially the Soviets). Never mind that previous generations stretching all the way back to the beginning of recorded history have also been involved in warfare as a means of cultural survival. The problem with all of this is it holds up as a gold standard a generation who proved itself by bravery under fire and force of arms. The implication then becomes if future generations wish to be great, they have a clear model in which to follow.

I’m drawing a connection here. As an American I live in a society where we authorized 700 billion dollars for the 2019 defense budget. We have also hit a point where everyone who has served in the armed forces is automatically a “hero”. At some point, we really have to put the breaks on and stop, full stop, and acknowledge that there’s a whole lot more to our national identity than martial prowess.

So yeah, I think it’s time we stop referencing the 40’s . We do it so much that it’s become lazy. It’s not helping our national identity at all. Maybe it’s time to subtly steer our sense of national identity toward appreciating moments when we we made great leaps in the field of science and experimentation, to achieving that which was though to be impossible. We do that enough and maybe we’ll start rethinking our criteria for the term “hero”.

So I want the pilot to fly a jet, wear a metallic suit, and look whole helluva lot like a test pilot.